Dethroning TCP From The Web?

Latest Revision: 27th of December

Prerequisites

The content of this post assumes knowlege of basic networking concepts such as the OSI model and how the HTTP protocol works to fetch and serve web content.

Introduction

Ever since Tim Burners-Lee created the World Wide Web, the Transport Control Protocol (TCP) has been the main and up until very recently, the most obvious option for transporting Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) web exchanges. Understandably, TCP was the transport protocol of choice given that the available options were limited between UDP and TCP, where UDP alone is a lightweight protocol that misses most of the features that the web desires.

Over 30 years have passed since the web was first available to the public domain and since then, it has evolved to become much more complex. Parallel to the increasing complexity of the web, the HTTP underwent several revisions (HTTP/1.0, HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, and lately HTTP/3 ) for simplicity we will refer to them as H1.0, H1.1, H2 & H3. TCP on the other hand, a much older protocol, relatively remained unchanged and only had minor tweaks over the years for reasons that will be elaborated further in the coming sections.

Regardless of this fact, TCP proved to work well overall in the web domain for so many years that to this day, web traffic mostly continues to use it as transport. Nevertheless, the evolution of the HTTP protocol across its revisions eventually emphasized major flaws with TCP that led to its complete replacement from the HTTP protocol stack. Most recently, H3 officially marked a new era for web transport where TCP, the transport protocol previously synonymous with the web, is replaced with QUIC.

As with every new technology, we are typically only exposed at first to its marketing, design and promises but eventually, what matters is how it performs. In an effort to answer this post’s title, the following text will first go through the context that led to where we are today with QUIC, then briefly discuss QUIC’s design, and lastly, the extent to which the promises are projected into practice and what that means for the future of the web.

Background

Uncovering TCP’s limitations

In the early days of the web, there were relatively few requests occurring in a single web transaction, sometimes a single HTTP request to fetch the HTML page is all that was needed to take place. Web pages were much simpler than what we see nowadays and as a result, early HTTP versions were sufficient for that purpose. However, if we look at how HTTP worked in early versions and continued to evolve, we can understand how future requirements of the web could not be fulfilled by the same underlying technologies. In the following subsections, HTTP’s evolution is explained to establish a better understanding of how we got to this stage.

HTTP/1.0

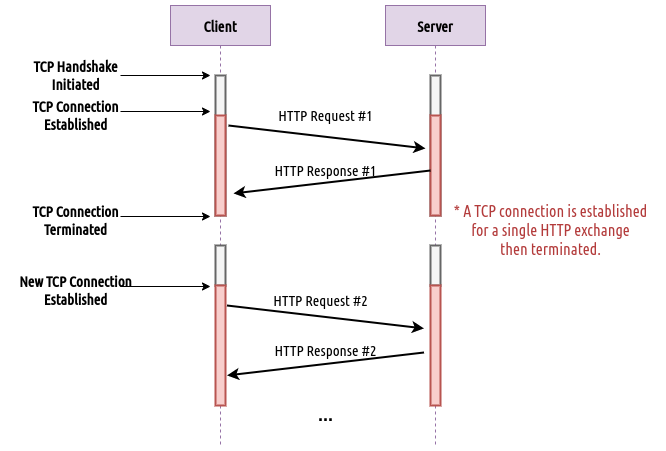

H1 was the first HTTP version standardized by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in 1995. The specifications of how web exchanges operate are illustrated in the figure below.

Fig 1: Timeline illustrating a H1.0 exchange, note that the TCP connection only serves a single HTTP request.

Fig 1: Timeline illustrating a H1.0 exchange, note that the TCP connection only serves a single HTTP request.

As presented above, in a typical H1.0 exchange, a TCP connection is established to facilitate the transport of a single HTTP exchange (HTTP Request & Response) and then immediately terminated. This means that for every HTTP exchange the client will need to establish a new TCP connection with the server which does not seem effective nevertheless, it was sufficient enough for fetching simple static sites in the early days of the web. However, it is obvious how limited and unscalable this approach becomes if more HTTP exchanges are to take place. Hence, the arrival of H1.1 just a year later.

HTTP/1.1

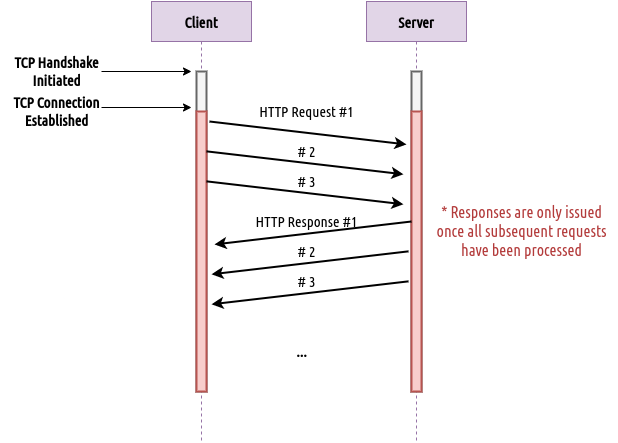

What H1.1 mainly aimed to achieve was the ability to consume TCP connections more efficiently, specifically by exchanging multiple HTTP exchanges per TCP connection as illustrated in the diagram below. This approach was instantly more effective than H1.0 since TCP connections are now kept “alive” until all needed HTTP exchanges are completed.

Fig 2: H2 allows for multiple requests to be sent in the same TCP connection.

Fig 2: H2 allows for multiple requests to be sent in the same TCP connection.

More so, this version of HTTP introduced the concept of Pipelining which allows the client to send subsequent HTTP requests without needing to wait for each corresponding response to be processed. This also led to notable performance improvements since in previous versions, subsequent requests could not be sent until the response of the previous request has been received and processed.

Nevertheless, H1.1 still left room for improvement. Mainly in the fact that from the server’s perspective, responses are not sent until all prior requests are processed. For example in the figure above, even though request #1 arrives first, it is not responded to until request #3 has been processed. This is not ideal in the web domain as some requests can be unrelated to others and for that reason, they should not be slowed down by later requests.

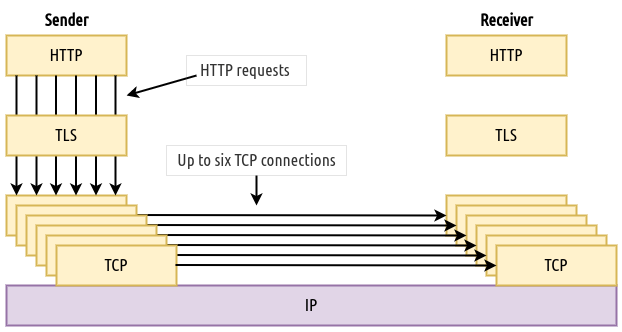

To get around this issue, specifications suggested that clients can establish up to 6 TCP connections with a server as shown in figure 3. This way, subsequent requests can be assigned a dedicated TCP connection, which will make HTTP requests sent in different TCP connections independent of the rest allowing the server to respond to them faster.

Fig 3: H1.1 client can establish six TCP connections to enable the receiver to respond independently to the transmitted data in each connection.

Fig 3: H1.1 client can establish six TCP connections to enable the receiver to respond independently to the transmitted data in each connection.

This however was not an efficient solution mainly because of the high resources that servers require to maintain up to 6 TCP connections per client. Despite the inefficiency in this regard, H1.1 worked well and was not succeeded until about a decade later. The arrival of H2 enhanced the performance and efficiency of web exchanges but also shed light to major TCP limitations that eventually led to the development of QUIC.

HTTP/2

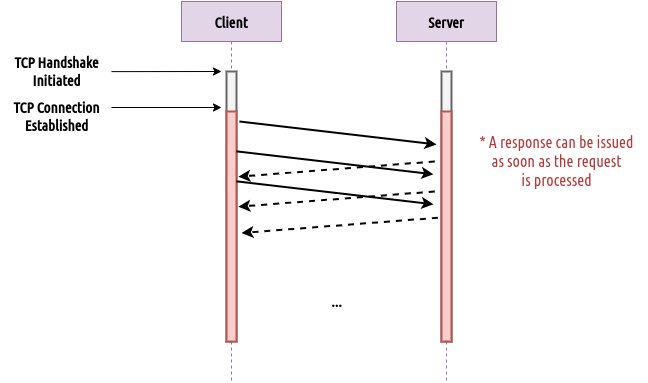

Working around the previous version’s limitations, H2 implemented the concept of Multiplexing that introduced independent streams for HTTP exchanges that can share a single TCP connection. This way HTTP exchanges can be processed independently without the need to establish multiple TCP connections as done in H1.1.

Fig 4: H2 requests can be uniquely identified allowing the server to respond to them independently.

Fig 4: H2 requests can be uniquely identified allowing the server to respond to them independently.

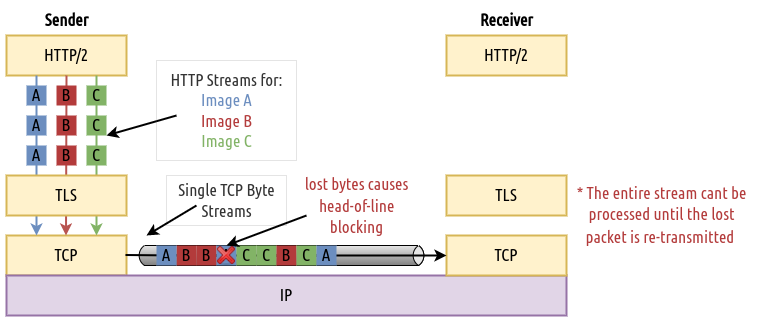

Nevertheless, the performance benefits of H2 could not be fully realised due to TCP’s byte-stream view of data that it receives from other layers. This means that data in independent H2 streams at the application layer will be interpreted as a whole stream of bytes by TCP at the transport layer as shown in the following diagram.

Fig 5: The H2 streams are treated as a single stream of bytes at the transport layer.

Fig 5: The H2 streams are treated as a single stream of bytes at the transport layer.

The important aspect to grasp from the illustration above is how the three independent HTTP streams (A, B & C) are batched together and sent in-flight as a single stream of bytes at the transport layer, where in the case that a byte in that stream is lost, the entire stream awaits re-transmission before being processed at the receiver. This behavior is referred to as Head-of-Line Blocking. Ultimately, this observation highlights an important performance bottleneck:

To fully reap the benefits of multiplexing at the application layer (which is what H2 did by introducing streams), multiplexing must also be supported at the transport layer.

At this stage, we can begin to see that for the web to continue to enhance its performance, the focus needs to shift from the application layer to the transport layer specifically TCP which is where the main limitation lies. To address this limitation, the potential solutions were mainly among two pathways:

-

Improve TCP’s implementation so that multiplexing is supported at the transport layer.

-

Develop a new protocol that will understand the concept of streams therefore supporting multiplexing and have it use UDP as a substrate (for reasons explained in the following).

It might first seem that enhancing an established protocol is a more efficient and reasonable solution rather than developing one from scratch. However in this case it is the opposite. TCP is a kernel-side protocol that has been used in the internet for over 40 years, to introduce a major change to such an established protocol would practically mean changing TCP’s implementation in major kernel vendors. This would also include deploying changes to Middleboxes across the internet and not just end-systems which is simply not practical in today’s networks. More so, even if global scale support was initiated, it will take years to see wide-scale deployment which doesn’t match the rate at which the web is evolving. This challenge that stagnates the enhancements of a protocol is sometimes referred to as Protocol Ossification which is a topic worthy of its own post.

Eventually, the second pathway prevailed as a more practical option that involves having our desired features like multiplexing, implemented on top of a lightweight established transport protocol like UDP to avoid stagnant compatibility efforts.

Emergence of QUIC

Development efforts kicked off at Google around 2012 to develop a new protocol which we know today as QUIC. Initially, the focus was on developing a multiplexed transport protocol that will help boost HTTP’s performance potential. Later in 2015, the QUIC efforts at Google were passed to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) which desired to make QUIC an independent transport protocol that can benefit other application layer protocols and not just HTTP.

It is important to highlight that when talking about “QUIC” we are typically referring to the standardized version of QUIC that occupies the content of RFC 9000. Where as the initial implementation of QUIC that was developed at Google is known as gQUIC. There are differences between the two implementations however, after the migration to the IETF, Google also worked to tune their implementation to support the standardised QUIC specifications.

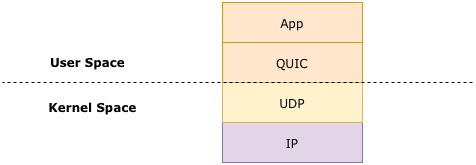

Although QUIC is a “transport protocol”, it resides in user-space unlike traditional transport protocols such as TCP & UDP. As mentioned earlier, this is a workaround for the ossified transport layer to allow QUIC as a protocol to evolve in the future with ease.

Fig 6: QUIC’s protocol stack highlighting the user-kernel space division.

Fig 6: QUIC’s protocol stack highlighting the user-kernel space division.

QUIC at first seems like a new protocol that is just TCP with multiplexing, but that is not entirely the case. It was also equipped with a set of features that can enhance the experience of web clients. The following is a brief overview of some of those features:

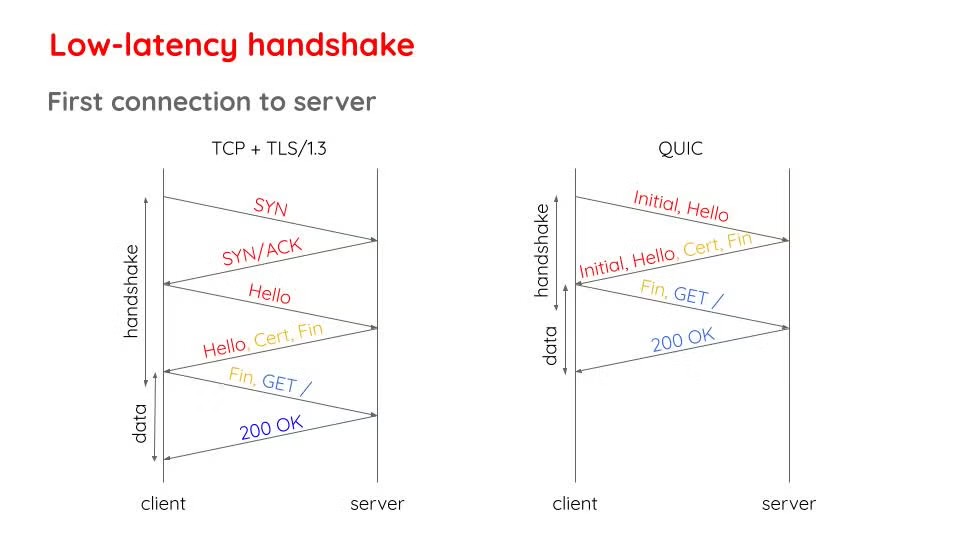

- Reduced Connection Handshake Latency

A significant part of the web experience is related to the time it takes to establish a connection with servers because that determines how fast can we start sending application data. Especially nowadays where it is likely that even the contents within a single web page will be served from varying locations, a client can be expected to require establishing multiple connections while surfing the web. In this regard, QUIC costs at most a single round trip before being able to send application data whereas with TCP, it takes a couple of round trips (could be more if TLS 1.2 or an older version is being used).

Fig 7: Comparing handshakes of TCP (with TLS 1.3) against QUIC’s handshake that requires fewer round trips [1].

Fig 7: Comparing handshakes of TCP (with TLS 1.3) against QUIC’s handshake that requires fewer round trips [1].

- Zero Round Trip Time (0-RTT)

As described above, QUIC takes a single round trip at most but in certain cases QUIC also can allow clients to send application data from the start before receiving anything from the server. This does however require the client to have either had a previous connection to this server or set predefined configurations.

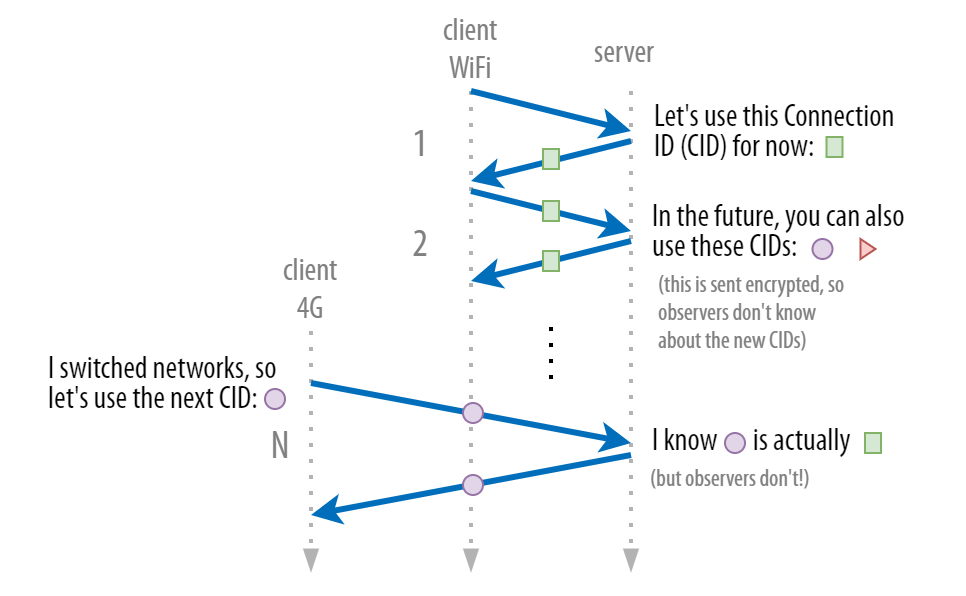

- Connection Migration

Unlike with TCP, a QUIC connection is not dependent on the IP of the client device. Meaning if for instance, a client switches from Wi-Fi to a mobile network midway through a QUIC connection, that connection will be carried over and not terminated. Typically with TCP, if the IP address changes, the connection will close and have to be re-established.

Fig 8: Illustration showing how Connection IDs (CID) is negotiated between the client and server to avoid having to open a new connection if the client changes network [4].

Fig 8: Illustration showing how Connection IDs (CID) is negotiated between the client and server to avoid having to open a new connection if the client changes network [4].

The above are just a few of the main additional features of QUIC that were put in place to improve the experience of low-latency demanding services and cases where the client’s underlying network may change. QUIC also built on years of experience with testing TCP and enhancing aspects of transport functions like loss-recovery, congestion control and others. Fundamentally, QUIC offers a lot more than what will be covered here (see RFC9000) to avoid dragging this post longer than desired.

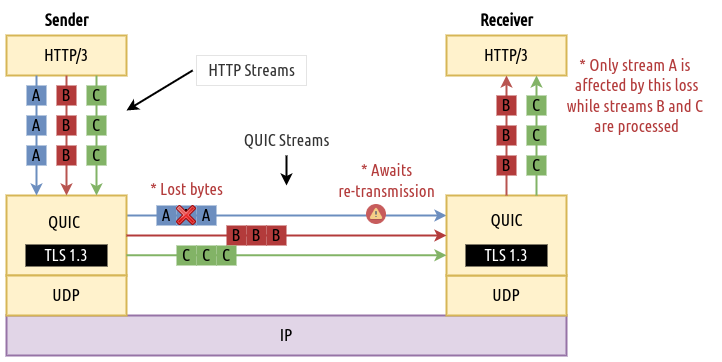

Focusing on the most relevant feature of QUIC to this post, the following diagram illustrates how it is designed to be capable of multiplexing at the transport layer. When each of the HTTP streams is passed down to QUIC, independent QUIC Streams are assigned at the transport layer. This then enables the receiving end to distinguish between the incoming streams of bytes and consequently, be able to process and pass them to the application independently as soon as they arrive, thereby achieving the benefits of multiplexing. Comparing this to the previous example in H2, QUIC can assign each of the images an independent stream and so if one stream relating to image A is affected, only the processing of that stream awaits retransmission while streams of image B and C are processed therefore avoiding the head-of-line blocking problem with TCP.

Fig 9: QUIC streams are uniquely identified at both ends enabling the server to handle each request independently of the state of the others.

Fig 9: QUIC streams are uniquely identified at both ends enabling the server to handle each request independently of the state of the others.

Importantly note that in this case UDP being a well established protocol, simply acts as a vehicle for QUIC to traverse the internet infrastructure. After all, UDP operates as usual in a “best-effort” manner while all the other desired features for web exchanges (retransmission, packet reordering and other) are delegated to QUIC. Unlike with TCP, UDP does not interfere with QUIC’s streams by not interpreting them as a single stream of bytes.

With that capability to multiplex at the transport layer, H3 is now officially a standard protocol RFC 9114 that swaps out TCP from the HTTP protocol stack for QUIC and UDP.

Okay, all this theory sounds great but how does QUIC perform in the real world?

Performance Tests

Fortunately, QUIC has been around for some good time now and a decent amount of tests have been conducted to investigate QUIC’s performance in practice. In the following text, several distinct studies and experiments will be discussed listing their main observations.

To begin with, one of the early studies testing QUIC’s performance as expected came from Google in 2017 [3] and compared H3’s performance against H2 on metrics such as video rebuffer rates, video playback & search latency leading to the following observations:

-

As expected, QUIC outperformed TCP with handshake latency since it takes fewer round trips to complete. However, it is important to note here that the margin of improvement also increases as the minimum Round Trip Time (RTT) increases. This means that for connections where the RTT is relatively large, the performance improvement due to the shorter handshake is more noticeable.

-

In terms of search latency (the time from entering a search term till all the results are loaded), H3 outperforms H2 which is also attributed to the reduced handshake latency that does factor in this metric since connection establishment is part of fetching the search results. Here the improvement margin also increases as the RTT does.

-

Using QUIC, Video Latency (the time from selecting a video till the start of the video) and Video Rebuffer Rate are reduced. The first is also impacted by QUIC’s low handshake latency and the 0-RTT feature which the study claims that around 85% of connections to YouTube benefited from. The latter is insensitive to handshake latency and more attributed to QUIC’s more resilient loss-recover mechanism.

-

QUIC performed equivalently to TCP and sometimes worse in high bandwidth connections which was attributed to client-side CPU limitations. QUIC clearly showed to benefit high-loss & high-delay networks showing significant improvements against TCP in locations like India that have the highest RTT and retransmission rates.

-

Running QUIC was in some cases consuming CPU resources 3.5x what TCP recorded due to it running in user-space.

Building on the last observation above, another notable experimentation came from Fastly in 2020 [2] looking at QUIC’s computational cost which has been known for a while to be one of QUIC’s major drawbacks. The experiment looks at various approaches in which this computational cost can be minimised in comparison to TCP. They outline the following findings.

-

QUIC is typically much more consuming of CPU resources due to residing in user-space nevertheless, there are possible tweaks that when implemented together can make QUIC almost as computationally costly as TCP. The main bottlenecks and workarounds for QUIC’s computational inefficiency are covered below:

- High number of Context Switches

Due to QUIC’s transport logic residing in user-space, typically every QUIC packet needs to be passed between the user & kernel space through a context switch.

Workaround: UDP Generic Segmentation Offloading (GSO).

GSO offers a way for a user-space app to coalesce QUIC packets and pass them together to the kernel as a single virtual packet to reduce the number of context switches required. So say we have 20 QUIC packets that need to be sent across, instead of needing 20 context switches (1 context switch per packet) we can group 10 packets and pass them over once, ultimately needing a total of 2 context switches (1 context switch per 10 packets).

- Acknowledgment Rates

TCP handles all acknowledgments (ACKs) logic at the kernel, QUIC on the other hand takes care of that also in the user space. The higher the acknowledgment rate the more data copies are needed.

Workaround: Delaying ACK rates per received packets.

QUIC specifications suggest that an ACK is sent per two received packets, this experiment has shown that reducing the ACK rate to one per 10 received packets has notably reduced computational overhead. Note that this workaround can have undesired consequences such as reducing the connection’s throughput.

- Packet Sizes

A small packet size would mean more packets are needed to transfer a piece of data which subsequently increases the required number of context switches as described in the first point.

Workaround: Increase packet size to reduce the total number of packets sent in a QUIC exchange (preferably set the packet size according to the received packet size from the sender to avoid getting dropped due to path limits).

Lastly, a study from Brown University [5] investigated the performance of production QUIC among a few large-scale implementers (Google, Facebook & Cloudflare). This particular study focused on investigating the root causes behind QUIC’s performance enhancements and also comparing the performances among the implementers in which they observed the following:

-

QUIC’s low latency handshake & 0-RTT provide notable performance enhancements for small payloads only and are not the focal source of improvement over TCP implementations. With larger payloads (over 100KB), QUIC’s performances are almost equivalent to TCP and could be worse depending on the choice and implementation of the congestion controller.

-

The implementation of the congestion control algorithm majorly impacts QUIC’s performance. This means that implementers using the same congestion control algorithm i.e. Cubic or BBR, may still extract significantly different performance results if their implementations are not alike.

-

QUIC’s design which allows for flexible implementation leads to significant inconsistencies in performance between implementers.

Keeping the above in mind, how does the future of the web look like with QUIC in play and what does it mean for implementations still using TCP as transport in the web domain?

Concluding Thoughts

In summary, the web’s increasing performance demands have shed light on various drawbacks of TCP. Coupled with the challenges of the ossified transport layer, how we implement transport functions has changed notably. Embodied in QUIC, transport functions are moved to the userspace while using UDP to traverse the current infrastructure. With the standardization of H3, TCP is no longer the obvious option of transport for web exchanges. Ultimately, looking at what we know today about QUIC and how it performs in production, the following are my concluding remarks concerning where QUIC and the web domain are heading.

- Overall QUIC achieves what it was designed to do and produces impressive results for latency-sensitive services.

On average, QUIC outperforms TCP implementations and although this improvement can be minimal in high-bandwidth networks, the margin of improvement is significant in high-loss/delay conditions. This enhances the experience of web clients in many parts of the world that do not benefit from high-quality networks that previously suffered due to depending on an ossified legacy technology like TCP.

- QUIC’s computational cost will likely remain higher than TCP as long as it resides in user space.

There isn’t a reliable & consistent solution to QUIC’s computational inefficiency than to have it implemented in the kernel. The workarounds attempted by Fastly have shown promising results but the proposed modifications themselves are only applicable to varying degrees depending on either the client, server or network capabilities. For example, increasing packet sizes depends on path limitations which can differ from one client to another, the higher the packet size the greater the risk of it getting dropped. Additionally, delaying ACKs has been shown to reduce QUIC’s computation but it can also lead to reducing a connection’s throughput which will subsequently affect the performance. Eventually, such workarounds come with tradeoffs and do not promise consistent results.

Although implementing QUIC in the kernel is technically possible, it is not so practical or feasible at least at this point. As mentioned in earlier sections, bringing a major change to the transport layer is a challenging task, due to the global and ubiquitous effort that is required and also the strong use case that QUIC currently lacks. Even though QUIC has shown great improvements over TCP implementations, the change is not crucial. Just to draw a parallel, the use case for supporting IPv6 globally (to resolve IPv4 exhaustion) is stronger than it is to support QUIC and as I write this post, IPv4 still dominates the internet over 25 years since the first specifications were published. I’m not saying QUIC will require as much time but regardless it will take a considerable amount of time and effort.

- The QUIC protocol remains in its early days and the current discrepancy in its performance will reduce over time.

QUIC’s flexibility has its pros and cons, the cons as noted above lead to varying performance results between implementers, even those using the same configurations and choice of congestion control algorithms. The pros are that QUIC is relatively still in its early days and fine-tuning it is practical. The current open-source and from-scratch implementations of QUIC will over time become battle-tested and normally, such implementations will change to become more unified as we learn more about the protocol’s behavior in production environments.

- TCP is nowhere to go in the web domain.

Finally, despite QUIC’s promising performance gains and adoption so far, it’s really difficult to see TCP implementations reducing drastically in the web domain, especially in the short term. TCP is a robust battle-tested protocol that continues to serve the majority of web traffic. Even today, it is typical for QUIC clients to fall back to TCP when issues are encountered. Ultimately, QUIC will remain a novel and viable option for services not just on the web front but TCP is here to stay.

References

-

Iyengar, Jana. Modernizing the internet with HTTP/3 and QUIC, 30 January 2020, https://www.fastly.com/cimages/6pk8mg3yh2ee/4AbXvmMTnu0kCc8t1063Zx/c878838fe1fdeff64761dba1a4387d3f/quic-image1.jpg?auto=avif.

-

Iyengar, Jana, and Kazuho Oku. “QUIC VS TCP: Which Is Better?” Fastly, 30 Apr. 2020, www.fastly.com/blog/measuring-quic-vs-tcp-computational-efficiency.

-

Langley, Adam, et al. “The quic transport protocol: Design and internet-scale deployment.” Proceedings of the conference of the ACM special interest group on data communication. 2017.

-

Marx, Robin. How QUIC Helps You Seamlessly Connect to Different Networks. Pulse, 4 July 2023, https://pulse.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/3-migration-multi-cid.png.s

-

Yu, Alexander, and Theophilus A. Benson. “Dissecting performance of production QUIC.” Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021. 2021.